My Dad Believed in the Manly Art of Self-Defense. No Boxing Gloves for Grampa

#selfdefense #boxing #grandfather #grandchildren

May 28 is the anniversary of my father’s death. I wrote about the days leading up to his death in an earlier article for this web site.

My dad died on May 28, 1980, after a debilitating series of small strokes that diminished him in degrees until he was barely there for any of us. We took turns at his bedside while he held on in a coma, struggling for his next breath. One day, when I was in his hospital room with him, a nun walked up behind me.

“It’s always so difficult,” she said in a tone of voice that let me know that she had been at the bedside with many like my dad.

“It’s so hard to see him this way,” I responded, “knowing that he can’t come back, yet he fights on and on.”

She placed her hand on my shoulder. “I know. I know.”

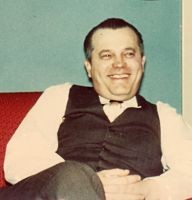

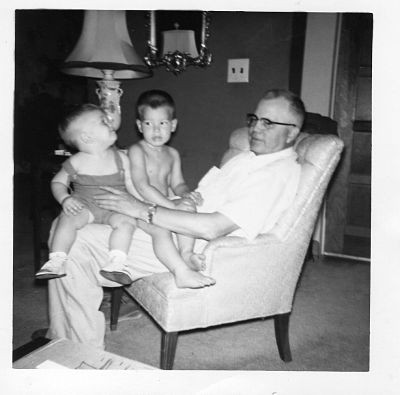

Anyone who knew my dad would know that he would put up a fight. Dad was not pugilistic, but he believed in the manly art of self-defense. He bought boxing gloves as big as hassock cushions for my brother and me so that we could learn to box. He would put on a pair himself, get down on his knees, and square off with us one at a time. Years later, I watched the home movies of these bouts. I would flail away at him and he’d block every one of my swings. Then tap. Tap. He’d strike with a pointed jab that would zip right through my guard and bop me on the nose, then the chin. My defenses were always in total disarray because my attacks on him were so wild with abandon. I wanted to hit him, I remember that, but my blows never landed and as fatigue overtook me, I would concede defeat.

“Never give up,” he would say taking off the gloves. “You can always get a lunch even if the other guy is getting a meal.” Or, “So you lose. Get a couple of punches in on him and the other guy will know enough not to mess with you again.”

He put up a boxer’s punching bag in the basement and demonstrated how my brother and I should practice with it. Tappity, tappity, tappity, his bare fists turned the bag into a blurred pendulum as he stood up to it. The bag rebounded back into his next punch and whipped back in forth in a rhythmic frenzy. Whop. I’d hit it once, and it would still be hanging like a large bloated pear. “Harder,” Dad would yell. Whop, once. Whop, again. “Well, work at it,” he’d say and go back up stairs.

I was not a fighter. The few times I did mix it up with any other kid, I lost. I hated fighting. I never felt angry enough to fight. All I ever felt was fear—fear of getting hurt. After a loss, my pride sustaining more bruises more than any part of my body, I’d retreat home downcast, sometimes even crying. One time Dad, in total disgust with me, took me by the back of my collar, hauled me back out into the front yard where my adversary was still gloating over his victory, and demanded that both of us resume combat. “Go ahead,” Dad shouted. “Stand up to him like a man.”

I couldn’t of course. I could hardly see my opponent for the humiliating tears in my eyes. For his part, my would-be foe looked back at me with more sympathy than I thought him capable of feeling and then hit me squarely in the mouth, splitting lower my lip. That knock-out punch spelled defeat for Dad, also. He turned and walked without a word back to the house. Later that day, I heard him tell Mom, “That kid needs to learn how to stick up for himself. He can’t run home crying like that every time he gets into a scrap or they’ll run him right off the block.” A good thing for me that nobody ever tried. Somehow I reached maturity without without ever needing to prevail in a do-or-die scrap with anyone. Despite my dad’s efforts, I was a coward. Although I turned in respectable efforts as lineman on my high school championship football team, I have remained a devout chicken to this day.

I have told these stories to friends many times. “How awful,” some remarked. Yet, I do not think it so myself. He was my dad. He thought it was important for me to learn how to defend myself. Perhaps fighting was far more commonplace in the age when he was boy. His efforts were in vain because he never reckoned with my marrow-deep fear of pain and the conviction that I was going to lose anyway, no matter what I did. Besides, I didn’t want to hurt anyone. It just wasn’t in me. To this day, I will go to considerable lengths to avoid the possibility of physical pain. Dad, on the other hand, accepted it as part of life.

“So it will hurt for a little while,” he would say.

Not me, I’d say to myself. Not me. No way.

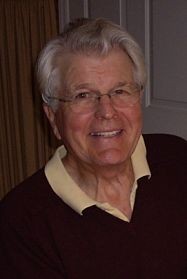

I loved my dad. I revere his memory. I am now within two years (posted 2013) of his age at the time of his death. A child creates an image of his or her father. And like any impression we form of another, a child interacts and reacts to the image rather than the man himself who is, as we may eventually acknowledge, fallible and even weak at times. For their part, fathers often prefer to be the man behind the curtain and continue to project the image of the all powerful Dad* rather than risk vulnerability and reveal themselves. The real loss to both the child and the father in the failure to forsake the images and become available to one another—as a person of strengths and weaknesses, wise and foolish, vulnerable and sometimes unaware. Dad and I got very close to a man-to-man friendship before he died, and I will always be grateful that he had the courage to make himself available to me. He enabled me to reciprocate.

* The allusion here, of course is to The Wizard of Oz. I wanted to create a link for it but Amazon hogs all the Google searches.

This is the first in a series that I plan to write about my father. Please check back with my web site form time to time for my subsequent posts. Meanwhile, while you are here, please consider entering a comment below. I also invite you to thumb through the other pages of my web site. Thanks for dropping in.