Reviewers Cannot Make Allowances When Writers Self-publish Without an Editor’s Help.

If a person wants to become an electrician or plumber, entrance to the trade is gained by becoming an apprentice. Before being licensed, the apprentice takes classes and works with an experienced journeyman until a command of the basics is tested and certified as having been achieved.

Not so for writers, however. Aspiring authors are urged to study the craft, memorize the rules of grammar, seek the advice of experts, and submit their work to editors and proof readers, but none of these steps is required. Writers, unlike trades people and performance artists, can declare themselves accomplished. Many introduce their work, unschooled as it is, to the judgment of the marketplace and reviewers in the hope that it will be praised, and if not praised, at least treated charitably.

The amateur who forsakes the rigors of learning the craft places the reviewer by default in the role of pointing out the flaws in a work. The reviewer becomes a teacher rather than a critic because the work being considered is almost entirely lacking in literary merit.

As a reviewer, I don’t enjoy being put into this position. Crudely executed books are only possible in a system that allows authors to go directly into print. Publishers available to writers who decide to self-publish do not care about the quality of the work submitted to them. They make a buck whether the book sells or not. The time might be right for a publisher to break away from the pack by setting and maintaining minimal quality standards. In that way, a reputation could be built that would ultimately prove to be a marketing advantage. Readers would recognize the brand name as a quality hallmark. Writers who would want to be favorable showcased would be more likely to submit their work.

Disdain for the Art . . .

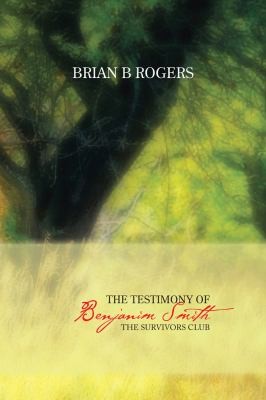

Brian Rogers’ book, The Testimony of Benjamin Smith: The Survivors Club, is regrettably a case in point because he fails to demonstrate an understanding, let alone mastery, of the fundamentals of good writing. The basic unit of any composition, after the sentence, is the paragraph. Rogers doesn’t know how to write one. In writing dialogue, every time there is a change in the character speaking, the writer must begin a new paragraph. Rogers lumps quotations by different speakers together in the same block of text – one of his would-be paragraphs. These and the other elementary rules of grammar and composition are not difficult to learn. Refusing or failing to do so is simply not acceptable and reflects a degree of disdain for the art of writing, whether intentional or not.

Rogers brings a raw talent as a raconteur to his narrative. Most readers have listened to a family elder go on and on about what life was like growing up. At first, the tales may be somewhat engaging. A certain wit evokes a smile now and then and perhaps a chuckle. But as the speaker prattles on and on, the awareness dawns that the stories are not intended to entertain the listener at all. The monologue is for speaker’s amusement who drones on oblivious to the discomfort of the listener.

Also tiresome is Rogers’ dwelling on the inconveniences and afflictions of old age. Nobody cares about forgetfulness, aches and pains, insomnia or a fondness for brew. With age, hopefully, comes wisdom and with wisdom, insight into human behavior and why we do the things we do – whether out of desperation, foolishness or passion. The antics of Rogers’ characters are sometimes funny, sometimes cruel, often foolish but never complicated by pangs of conscience, uncertainty, or any hesitancy over the choices they make. The reader comes away with little insight into the any of the character’s feelings or motives.

First-person narratives are always tricky. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield comes to mind or Twain’s Huckleberry. When done well, readers meet an engaging narrator whose personality is presented as clearly distinct from the author. Some authors successfully narrow the gap between themselves and their narrators – Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, for example. Regardless of how narrow the separation becomes, however, readers remain aware that the author is distinct from the narrator presented in the work. In his book, Rogers is Benjamin Smith. His book is a memoir; not a novel.

Writing Does not Come Naturally . . .

Perhaps no amount of study would help this author overcome some of the shortcomings in his work. Writing does not come naturally to everyone any more than a talent for higher mathematics. But an editor’s advice surely would have helped shape the book into more presentable form.

It hardly seems fair to compare work of the hobby writer to the masters of their genre, yet that ultimately is the standard time will hold up to their work. I use Rogers’ book as an example, unkind as that may seem. I would not have reviewed it all except the author submitted it to bookpleasures.com in order to have it considered. Since I review for the web site, I feel obligated to deliver when I accept an assignment. I perhaps could have advised the Rogers in advance that I could not give his book a favorable review. He then could withdraw his request. Glenda Bixler did as much for me a few years ago when she received her review copy of Deadly Portfolio: A Killing in Hedge Funds, but her trouble with my book was the runaway number of proof reading errors, not basic grammar or the story line itself. I was grateful to her for suggesting that I withdraw my request and take steps to correct the problem, which I did by a complete editing of the work and by changing publishers. Upon resubmission, Ms. Bixler awarded five stars and praised the book in her review.

Making Allowances . . .

Fans of the theater do not expect amateur performances to measure up well against professional shows. They purchase their tickets fully mindful of the level of performance that they expect to see. They make allowances accordingly. Once readers tire of picking up books that turn out to be a waste of time, perhaps a suffix can be introduced to modify all genres in classifying books. Hobby might be appropriate. Invoking it, an author who chooses to self-publish declares that a named work is not to be held to prevailing literary standards. It would be understood that it was written for the author’s own amusement. In Roger’s case to illustrate, the genre would be designated, Biography-hobby. Readers would then be forewarned and be more inclined to accept a work on its own terms. Writers adopting the designation whose work proved worthy of more serious consideration would enjoy being promoted. Better that, certainly, than suffering the slings and arrows of cranky reviewers who refuse to make allowances for a book that is published just for the fun of it or for the age of the person who wrote it.