Divorce Makes Christmas Holidays Challenging.

#divorce #christmas #family

Divorce creates a crater in the continuity of life. It usually separates one parent from daily contact the children and the emotional security of being able to look back with detachment on all that transpired in their life as a family. Recently, I tried to review movie film of my young family that was taken 40 years ago. There I was, younger, beaming as I held up a Christmas gift to the camera. The sequence revealed two things.

I had donned a new bathrobe to prove the fit and pose the shot, but my staging struck me as dishonest to a degree. I wanted my wife to know that I was pleased with her gift. The first recollection led to the second. My wife made the robe because she could not afford to buy one. My gift to her was also modest. The toys scattered about for our children were the real cost of our holiday. For as much as we may have wanted things to appear differently, this was a slice of life at a time when happiness was not there. We were doing the only thing that we could at the time. We were making do.

There is difference between making do and being really happy. Happy people fall to sleep untroubled about the amount of money in the checking account or that last word from a critical boss. Happy people do not question whether their life is the one they would live if they could change it, if they could find a way to stop reacting to circumstances and shape a deliberate course toward the goals they wanted to achieve.

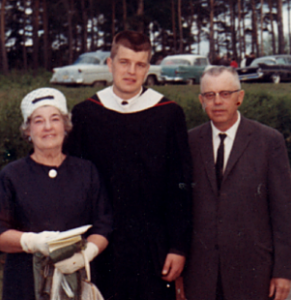

My mother and father married during the Great Depression in 1935. Dad graduated from the Creighton University Dental School in Omaha. He returned to his native state of South Dakota to set up practice. Getting established was very difficult. He needed equipment, implements, x-ray, and operating room supplies. The Midwest was experiencing the drought of the century. The economic depression reduced nearly everyone to poverty. He moved three times, from one small town to another, before his practice took hold.

My mother was the youngest of five daughters. She had no memory of her mother who died in an explosion a few months after Mother was born. The household, however, was wealthy. My grandfather owned several grain elevators in South Dakota. His fortune was carried off in dust storms of the 1930’s. Mother, however, remembered the comforts and privileges of wealth and felt deprived by circumstances.

To all accounts, my parents were not happy for the first 25 years or so of their marriage. But they made do. They muddled through. The phrase muddle through is defined by one source as “To push on to a favorable outcome in a disorganized way.” Thus muddling can be ennobling. One persists despite clear direction or knowledge to a fulfilling end.

They pushed on. Dad eventually prospered and rose to a position of prominence in our small, insignificant, little town in a quite insignificant, sparsely-populated state. . He rose as well as his profession. No one spoke of the terrible arguments that usually ended with him slamming the front door as he left the house and mother retreating to her bedroom (They did not share a bedroom for at least the last 35 years of their marriage.) We, the children, stood by for the most part. My sister, the oldest, on one occasion shouted, “Stop! Please, just stop it!” But it didn’t matter. The three of us felt estranged from both of them when the yelling began. We learned eventually that nothing would come of it. We would still be a family once tempers cooled. Life would go back to a fragile normal, but we never knew where the detonators were hidden.

The fighting finally stopped. Mom and Dad surrendered to destiny rather than to each other; a destiny that was being forced upon once it became amply clear their youthful aspirations were imperiled beyond rescuing. Whether they knew it or not, they decided to be happy. Dad jibed with cronies at the drug store lunch counter. Mother would sit on his lap and giggle. Resignation won out over desperation. Their fifth decade together launched into calmer seas. They played golf together and enjoyed their friends. Wintered as snowbirds in Phoenix. All of this despite the fact that there was no way they could have been happy with their adult children, but a favorable outcome, the ultimate goal compromised repeatedly over the years, was finally achieved.

Dad started to write a piece about his life. He began with the metaphor of a man and “a good woman” who had progressed up a mountain toward a peak where both could look down on the valley below and see the climb they had made. The shadow of the mountain itself shadow obscured much of the path they had taken, but to Dad it did not matter that he could not see every detail. He drew satisfaction from looking back. They had achieve a height that afforded perspective. That was all that mattered. Filling in the detail would have been too painful. They had made it through and the sun was shining now. (Without sun, after all, there would be no shadow) and their way forward was clear. He never finished the piece. Everything he had to say was in the first paragraph.

Mother attended to Dad on his death bed. “I saw those big brown eyes follow me into the room as I walked up to his bedside,” she told me one day upon returning from the hospital. “He knew me. I know he recognized me, but he didn’t have power over his speech. He just looked at me like a big child staring at somebody he loved. He loves me, Sonny. I know that he loves me.”

And so I looked at the film sequences of my beautiful children coming home from the hospital, first one, then the next, and the next until the last of the five arrived. Each takes a turn at splashing in the bathtub and running through the house gleefully naked. They grow and lope around at play, agile and full of grace. All this was taking place while their mother and I muddled through.

We never achieved our favorable outcome. Our marriage blew up after 19 years—a bitter, angry and hurtful end to our muddling riddled, with sleepless nights, extended bouts of severe depression, disorientation, crushing career disappointments, and risings day after day with the resolve to persist somehow in a life that I, and probably she, wished to change into the one we felt was intended for us.

Divorce ruptures all continuity in one’s life. Both partners begin again. It isn’t easy. Time, they find, has taken away many opportunities and the youthful energy to pursue them. The divorced couple burst back into the single life unprepared. Much of the maturing they would have experienced was postponed in changing diapers, chauffeuring progeny to music lessons and peewee football practice, and working overtime on jobs that neither would have chosen as a strategic step toward their career goals.

I began again and my life for the past 28 years feels like the one I that was intended for me. I helped raise a son. He is now married. She is a wonderful daughter-in-law and I have two lovely, energetic and affectionate step-granddaughters.

Lost for the longest time like abandoned satellites in the heavens overhead, however, were my own children. Where I had parents who stayed married until my father died when I was in my forties, their mother died ten years after we divorced while they were in their twenties. Even after my father died, I had a home to go to. They did not. They don’t even claim the same cities as hometowns. Slowly each has rebuilt a relationship with me. Not all the kinks are worked out yet. They may never be. Each sees me as a person independent of their mother, and I feel somehow slightly undeserving of any venerable status accorded other fathers who stay the course and complete the task of parenting.

The twenty-five years (posted in 2012) in my current marriage helped me realize by contrast what was missing in my first. Like discovering an injury after it was sustained, I needed to lance and drain away the infection that still festered in the mystery of how all of the hard work ended. I can’t find the young guy in the movies within me today. I don’t know him any more, but I have tremendous respect for what he tried to do. The contentment that is part of every day nurtures my healing. I can recall my own childhood with joy even though I recognize my parents were not the happiest together. I think my children are capable of the same thing. I believe in them.