Helicopter Parenting – Overparenting an Epidemic

#overparenting #childrearing #parental

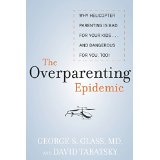

Helicopter parenting is the term for it. In The Overparenting Epidemic, George S. Glass, MD and David Tabatsky cast a wide net. The authors want to engage parents in an examination of their own parenting practices. Toward that end, the authors gently guide readers with self-assessment exercises and oblique anecdotes about some of the outlandish things others have done. They want readers to buy into the possibility that, yes, they too might be guilty of overparenting.

Because of the amount of time Glass and Tabatsky spend on explaining the syndrome, it is obvious they realize most parents will not see themselves in the mirror that is being held up to them. Parents with unruly, self-absorbed, disobedient children seem overly confident that their approach is the right one. They know. Everyone else is unenlightened. Perhaps they have formulated their helicopter parenting style in reaction to the way they were raised and that adds unlimited energy to their quest. The outsider, even if a family member, can only guess at what drives them. The subject of raising children is one of those volatile issues that almost never gets discussed.

Parents of today are the progeny of the boomer generation, a generation that has enjoyed the highest standard of living, even at lower economic levels, than ever before in our history. An era of technological abundance challenges parents today in a manner none could anticipate twenty years ago. A boy’s father years ago could help his son fix an electric train. Doing so provided an opportunity to be together and bond. A father today cannot be expected to repair a handheld device that puts television, games, a camera and a telephone into a child’s shirt pocket.

The authors give a quick history of child raising theories from Victorian times through the current time. Dr. Spock, the oracle of the mid-twentieth century, is cited by Glass as often misunderstood. They also provide a summary of the parenting styles; i.e. authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive.

Overlooking the phenomenon of self-deception, they offer a multiple choice instrument to help a parent-reader identify his or her parenting style. This is all very helpful material, but the cure only begins with the diagnosis. Commitment to making a change is the next step, and it may involve profound adjustments in how an adult sees the parenting role. Deep personal reflection, no small undertaking in itself, is part of the process. Some parents pour too much of their own well-being into succeeding at raising their child. To compensate for their own unfulfilled aspirations, some raise the bar too high for their youngsters. The consequences are never apparent in the moment. Children are to be delivered into adulthood as stable, productive, secure, happy individuals. With the finish line always in the future, denial comes easy. Until that day arrives, the parents know best, for good or ill, and push ahead ignoring the signs that common sense might tell them that they could be taking the wrong approach.

Helicopter parenting is not by definition permissive. It can be authoritarian, restricting children from activities their peers enjoy. No TV with parental approval. DVDs likewise. No fast food. The parenting style can be intrusive. The American culture is gross and course, and children need to spared from experiencing it. Parents become directive at school, at scouts, on the pee-wee sports field.

Parents can be permissive in some areas and non-negotiable in others. An uncle reported that he called his brother’s family during the Christmas season to extend his best wishes. “The boys liked their toys,” his sister-in-law reported.*

“Can I just say ‘hello’ to them?” uncle inquired.

“Hans. Dillon. Your uncle wants to talk to you. Come to the phone.”

A long pause.

“They said they don’t want to talk to you.”

“What the hell was I supposed to do then?” the uncle concluded in relating the event. “Tell her that she should put her little punks on the phone to teach them politeness and concern for others?”

“Their mother fixed three meals for six people when we were there,” a grandfather reported. “A separate meal for each boy because the mother knew that neither one would eat what was placed on the table for the adults. They also would not eat what the other wanted. Then, finally she set the meal for the adults. Whatever happened to ‘clean your plate?”

To counter the energy driving parents in their mission, Glass admonishes over-protective parents to “let go.” The regrettable truth is the message may not be enough to bring about the changes to help both parent and child find every day a happier place to be. Too many parents are driven to make up for the perceived failures of their own parents. They establish their own approach out of their own feelings of insufficiency and low self-esteem. Their children will do so much better. The tragedy is, of course, as children attain legal age, the unhealthy entanglement goes on and on. Glass, himself, suggests at one point that parents may need their own twelve-step program to disengage from an obsessive and damaging parenting style.

The damage done, as mentioned earlier, will become more apparent as the children move through adolescence and into early adult life. Those who have not learned who to relate to others, even if it means insisting on traditional conventions of polite behavior in the home, will continue to find it difficult to connect with others. “I might as well not bothered,” an aunt reported. “I hadn’t see those two girls in at least a year. There I was, in the hone, and they didn’t so much as say ‘hi,’ let alone give me a hug. They walked right by me as if I wasn’t there.”

Children who grow accustomed to having parents jump in and save them from failure or a difficult relationship often grow up expecting rescue rather than fending for themselves. They may have difficulty handling the complex feelings of failure when it occurs in real life — and failure is part of life. Glass urges parents allow children the freedom to experience life within the manageable dimensions of childhood, even if it means occasional disappointment and failure. The doctor has a contemporary message that echoes Kahlil Gibran, Your children are not your children. They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself. They come through you but not from you.

Children who are not taught to respect boundaries and the property of others may find it difficult maintaining proper decorum as adults. “The minute they entered the house,” one man reported, “my grandsons disappeared. We found them when we heard them jumping up and down on our bed in the master bedroom. Imagine! When I was a kid, you didn’t go into a parent’s or a grandparent’s bedroom, let alone jump up and down on it. ‘Get off the bed,’ my son ordered. They stopped jumping but they didn’t get off the bed. They sprawled out on it and looked at him. He didn’t say another word. I guess that was good enough for him. They didn’t obey him and he didn’t insist on it.”

Estrangement of grandparents from grandchildren often results when the family elders lose patience and find they cannot agree with the way the home is being run. “The inmates are in charge of the asylum,” one grandmother remarked in grim humor. At its most destructive, the rift can carry through to creating distance between the parents and the grandparents. “When they finally left,” one grandfather reported, “I needed to get massage therapy to take the knots out of my neck and shoulders. I was that tense. You can’t tell anyone what you really think, you know.” A conflict in values is the most difficult to resolve. It often results in limiting contact and remaining distant.

Author Glass appeals to parents to use common sense. He realizes that helicopter parenting is as damaging for the adults as it is for the children. He urges parents to take a minute and consider what they are doing. The chapters toward the end of the book give advice that is tailored to the various scenarios that can be found in the home of parent who does not let go, use common sense, and trust that their child has all the resources necessary to him or her to deal with the day-to-day world.

The weaknesses in the book lie not in the message but in the delivery. The book needs to be tighter. Examples of overparenting abound, to the point of numbing redundancy. Rhetorical questions are over used. Readers will consider Dr. Glass’ analysis and recommendations because of his experience and credentials. They don’t need to be goaded into thinking by a barrage of rhetorical interrogatives.

Most readers will get past these shortcomings because the book is timely and important. Glass avoids jargon and psyche-speak to produce a work that is clear in its message. Dr. Glass is preeminently qualified as the author and his work should prove to be an important guide to parents everywhere.

*Quoted statements are fictitious and for illustrative purpose. They are not from the author’s book.

This review initially appeared in somewhat reduced form in bookpleasures.com.

Thanks for looking in on my web site. While you are here, I encourage you to look through the other pages. Please feel free to enter a comment in the area provided below.