Fredric March: A Consummate Actor by Charles Tranberg — Reviewed by John J. Hohn

#fredricmarch #cinema #thebestyearsofourlives

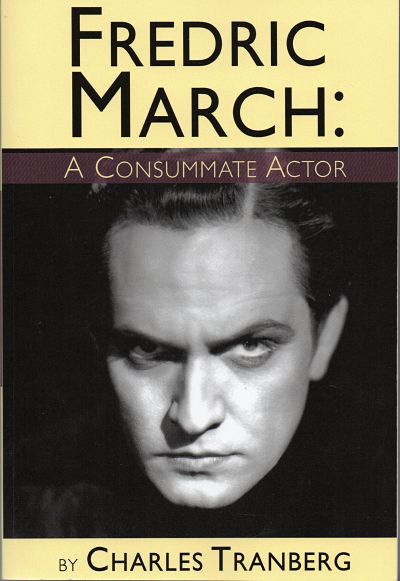

Charles Tranberg’s biography, Fredric March: A Consummate Actor, belongs in the library of every fan of theater and film in America. Tranberg’s masterful work follows March’s career from his Wisconsin boyhood through to his final triumphant appearance as Harry Hope in The Iceman Cometh released by 20th Century Fox in October, 1973. March was a man of the era and grouped among the many stars who, according to the author, “. . . excelled on both stage and screen.”

March, born Frederick McIntyre Bickle on August 31, 1897, showed an early interest in the stage. Graduating from the University of Wisconsin and after a short stint in the military, March moved to New York in the summer of 1920 to take a job in banking. Fate interrupted his corporate training in the form of an attack of acute appendicitis. During his convalescence, March realized he wanted above all else to be an actor.

Appearing alternately in Denver and New York, his big break came in the role of Tony Cavendish in The Royal Family by George S. Kaufman an Edna Ferber. Based loosely on the Barrymore family, Cavendish is modeled after John Barrymore. March’s imitation delighted the senior actor and for a time the character became a near alter ego for March. The role followed March into films when he appeared few years later as Norman Maine in A Star is Born. David Thomson, David O. Selznick’s biographer, described March’s performance in the film as “the most compelling thing in the film.” The Judy Garland/James Mason production may be the most widely remembered, but critics praise March’s performance as more subtle and compelling that Mason’s.

Tranberg’s book is extremely well researched. The author reproduces the text of letters, reviews, newspaper articles and the memoirs of peers and the author to track the March’s life from starting on stage to becoming a dominate presence in films. Tranberg is careful to let March’s peers fill in the picture of the actor. The book reads like who’s-who of the era with quotes from the best and brightest of the artists of the time.

Tranberg’s book is extremely well researched. The author reproduces the text of letters, reviews, newspaper articles and the memoirs of peers and the author to track the March’s life from starting on stage to becoming a dominate presence in films. Tranberg is careful to let March’s peers fill in the picture of the actor. The book reads like who’s-who of the era with quotes from the best and brightest of the artists of the time.

March breaks into movies as silent films give way to “talkies,” where his stage training serves him well. For all of his casualness in front of the camera, Tranberg cites repeatedly how diligently March researched his roles, studied his parts, and paid passionate attention to the slightest details. The actor knew his own weaknesses and admonished his directors to keep him from “hamming it up.” As a result, his performances were consistently praised as polished, subtle, suggestive, and restrained.

Tranberg is an accomplished writer. Fredric March: A Consummate Actor gains momentum as the central character’s career expands and the roles become more demanding. Readers may want to watch March’s movies again given the details the book provides about the actor’s preparation, direction and execution.

Big Break . . .

March’s big break comes when he appears in the 1932 release of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The film is a box office success. Tranberg pays attention to the technical challenges—no computers anywhere in sight—in making the film, not the least of which is the on-screen terrifying transformation of Jekyll into Hyde.

The transition from a refined, charitable doctor into a craven rapist-murderer is a curious clue to a side of March’s own personality that is mentioned again and again in the book by those knew the actor well. March, it turns out, was a groper and a womanizer, yet when his wife Florence was around he was a different man, as the author quotes Elia Kazan, “’Freddie was a child who couldn’t keep his fingers out of the cookie jar.’ When Florence did come over for a visit, March, as usual, became ‘another person.’” His wife tolerated his behavior, although it must have mystified some that a man capable of exquisite sensitivity on stage could be so disrespectful and invasive of the dignity of the women with whom he worked. With Florence, however, he was very protective, often lobbying to get her parts and promoting favorable reactions to her performances. Elia Kazan wrote of the couple, “I’d find, as I came to know him, that one of his pleasures was to be naughty and have Florence—his surrogate mother—chide him, ‘Now Freddie.’” Tranberg assiduously avoids commenting as the author on why March behaves as he does and never speculates about the formation of March’s personal character or the psychological forces that drive him.

Telling of the decades during which March worked are the contentious issues of censorship and blacklisting. During this dismal chapter in the industry, March is labeled a communist by irresponsible journalists, an allegation he forcefully denies. March and his wife were citizens of the world and thoughtful in articulating their liberal views. March ultimately won a retraction, but the rumor mill and vigilante press created a climate in which the author states that “it would be several more years before he (March) would be reestablished in motion pictures—mostly in leading character roles.”

Successes on Stage . . .

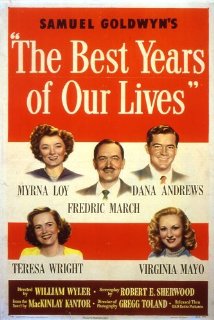

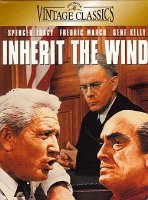

In addition to The Ice Man Cometh, March’s performances include many classics such as The Best Years of Our Lives, Seven Days in May, and Inherit the Wind. Tranberg rightfully spells out March’s successes on stage also. It is regrettable that all that is left of his performances are the rave reviews.

Tranberg writes in a conversational style that is easy to read. The attention to detail the author demonstrates in his research, however, does not carry over to his copy editor who failed to catch a number of glitches in the text.. The cast list for the 1935 release of Les Miserables, for example, has Charles Laughton as Valjean, whereas Laughton played Javert. At another point, describing March’s USO travels, the copy reads “. . . a special command performance for the Shah—with whom March also played tennis with . . .” In another passage, the text reads “March said that the retraction gave he and Florence great satisfaction. . ..” A few other typographical errors appear in the quoted passages.

Tranberg writes in a conversational style that is easy to read. The attention to detail the author demonstrates in his research, however, does not carry over to his copy editor who failed to catch a number of glitches in the text.. The cast list for the 1935 release of Les Miserables, for example, has Charles Laughton as Valjean, whereas Laughton played Javert. At another point, describing March’s USO travels, the copy reads “. . . a special command performance for the Shah—with whom March also played tennis with . . .” In another passage, the text reads “March said that the retraction gave he and Florence great satisfaction. . ..” A few other typographical errors appear in the quoted passages.

These blemishes, however, do not detract from the depth of the author’s presentation. Aptly titled, Fredric March: A Consummate Actor is a beautifully crafted history of a legendary actor and of the entertainment industry during his lifetime.

This review was initially published in a somewhat shorter form on bookpleasures.com. Thanks for visiting my web site. Please feel free to look through the other pages of my site. I invite you to comment in the area below about any of the content.