Civil Rights Leaders Dubbed Detroit a Model City in the 1960’s. Riots Changed the Face of the City..

#dettoit #detroitriots #civilrights #riots

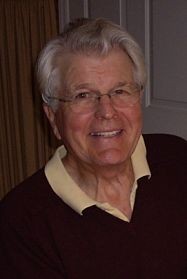

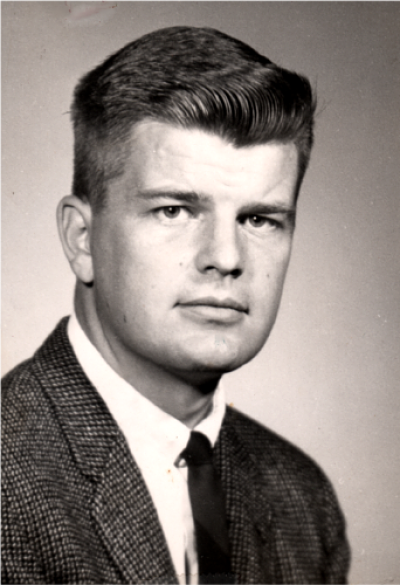

This is the second article in a series that began with my previous post about moving my family to Detroit in 1966. I concluded that piece with the statement “Nothing in our Midwestern upbringing prepared us (my wife and me) for the changes, the violence, the hatred, and the heroics that became part of every day in a troubled city like Detroit. At the time, Detroit was considered a model city for all the strides that had been taken in advancing the Civil Rights movement.”

I was an energetic supporter of the Civil Rights movement as a college student and as an English teacher at St. John’s Prep School, which is on the same campus as my alma mater, St. John’s University, in central Minnesota. There were no minority students in my classes. A visitor could spend a day on campus and never encounter a person of color. The few black students who attended the university were priesthood candidates from the Bahamas where the Benedictines ran a mission school (nice duty, by the way, life of poverty and all that). Blacks from the Bahamas were different from African-Americans, the implication being that they were superior to their brothers in the United States.

As White People Imagined

When minorities are not well represented in a community to put flesh and spirit into the issues by their presence, support for Civil Rights runs headlong into ignorance, fear and prejudice. In central Minnesota, Blacks were envisioned as white people imagined them. And what white people imagined was drawn from stereotypes because they had no contact with people of color to challenge their negative views.

I was too liberal for St. John’s which was the center of the ecumenical movement at the time. I was enthusiastic about the encyclical Pacem in Terris issued by Pope John Paul XXIII and joined in demonstrations against the Viet Nam war. St. John’s, I was told, was a land grant university and as such was obligated to require two years ROTC training for all university students. To oppose ROTC was to oppose St. John’s. I nevertheless had a hand in forming a group who picketed the spring review of the ROTC cadets.

There is no such thing as an ignorant skeptic. Skepticism takes root in how one interprets prior experience or processes what one is told. Skepticism, in other words, always struts about as if informed and knowledgeable. Idealism, on the other hand, usually takes root in a vision of what could be, the best of all possible worlds, and dismisses information inconsistent with the vision as irrelevant or ill-intended.

I lost

When the Headmaster called me into his office and suggested that I should go on to graduate school, it was his way of letting me know that I was being fired. The skeptics and doubters were going to hold onto their jobs. They supported the war in Viet Nam and believed Robert McNamara’s domino theory. They were suspicious of the Civil Rights movement. “He should have had more sense than to go down there,” the lay assistant headmaster growled after hearing William Ware, a black alumnus of St. John’s, speak to the prep student body, his face still bruised from the beating he took in a freedom march. Leaving the teaching profession meant that they had won. I had lost.

Our daughter Rachel was born June 26, 1964, just as I was offered a job by The Travelers Insurance Company, and I was slated to begin the training program as soon as I could get my family moved to Minneapolis. The Travelers office was located on the 12th floor of the Soo Line Building in the heart of downtown. Everything was new, and so was my attitude. I no longer wanted to stand out as an advocate for anything. I wanted to blend in and become part of the office community. I had five children to raise.

The Minneapolis office of The Travelers employed perhaps 300 people in the various departments. Not one person of color among them. Furthermore, a person walking around for an hour or two in downtown Minneapolis would see only a few persons of color. African-Americans made up about 10 percent of the population. Most of them resided on what was referred to as the “near north side.” Affluent blacks had moved into south Minneapolis, but resided mainly along Park and Portland Avenue. Native Americans constituted yet another small minority.

When I transferred to Detroit in the spring of 1966, I found it was a different city entirely. The Travelers office was much larger, occupying several floors of the Dime Bank building in downtown Detroit. African-Americans comprised at least one-third of the work force, and several held supervisory positions. I worked in the Office Administration Department (OAD), which was responsible for all the clerical functions in support of issuing casualty/property insurance policies, renewing them, verifying coverage when claims were reported, and collecting and reporting the premium in payment from the agency force. I was impressed with how comfortably whites and blacks got along. I half expected to encounter some acrimony and disharmony, but there was none. The management staff in all the departments, however, was comprised entirely of white males, with me the newest member among them. Everyone was addressed formally by last name with the prefix of Mister, Miss or Missus.

The Streets were Peaceful

I became accustomed to the fifty-fifty balance of whites and blacks on the streets of downtown. I rode the bus to and from work, sometimes late at night because of overtime requirements, and the bus route served the inner city neighborhoods. Grand Boulevard, for example, with all of its mansions of a earlier era converted into multiple dwellings, was almost entirely populated by African-Americans. I witnessed no discrimination on the bus. The streets were peaceful.

Sunday morning, July 23, 1967 was bright and sunny. Weeks before, working on weekends, I had started painting the wood trim and shutters to our brick home. I was on a ladder up against the front of the house, scraping the shutters to the upstairs windows when my neighbor, who owned and operated a service station at the foot of the Ambassador Bridge, pulled into his drive next door.

“I’d get down from there,” he called up to me to after putting his car in the garage. “There’s a lot of trouble on our side of town. These black devils kept showing up with glass jugs and gas cans and buying one . . . maybe two gallons at a time. Then the whole damn place was smoking. I shut down, just as the cops showed up to tell us to stop selling. You get down. Get your kids inside. If you have a gun, get it out where you can get at it.”

“I don’t own a gun.”

“I got an extra if you need it. You know how to use one?”

“I hunted a lot as a kid, but I don’t want a gun in the house. Thanks just the same.” Now that I was alerted, I could hear the sirens in the distance and smell the smoke. Southerly winds carried the stench of the Ford River Rouge plant into our neighborhood. Sometimes it was so strong that it would awaken me in the middle of the night. I learned to ignore it as best I could, but on this morning the sulfuric odor was overtaken by the acrid smell of smoke. I looked back toward the center of the city and black clouds of smoke were billowing up into the atmosphere.

All Hell Has Broken Loose

“Suit yourself,” my neighbor said turning back to his house. “All hell has broken loose and it’s not that far away. Who knows where they will be next.”

“What should we do?” my wife asked after we watched the television special broadcast.

“Just keep the kids in the yard, in the back of the house. We’ll keep an eye on things. The rioting is on our side of town and out this way a little, but it is still a long ways off. I think we’ll be OK.” As the day wore on, the news was worse and the situation was changing hour by hour. Rumors flourished. Even the television commentators would qualify some announcements as “unconfirmed reports.” I retrieved a baseball bat from the toy closet and put it by the front door. I thought twice about my neighbor’s offer to borrow his gun and decided against it.

Late Sunday evening, my manager called to say that the office would not open on Monday and that an announcement to that effect was going out on radio. “I’m worried about some of our people who live in that area,” he said, “and I sure as hell don’t want any white employees driving anywhere near there. We can check with each other this time tomorrow and decide what to do about Tuesday.” My manager lived in a western suburb of Detroit, miles away form the rioting. He went on to add, “They should have lined up ten or twelve of them against a wall and shot them. That would have put an end to it then and there.”

My wife and I tucked the kids into bed and took the table model television set up to our bedroom so that we could follow what was taking place. One thing sure, we didn’t expect to get much sleep.”

To Be Continued . . .